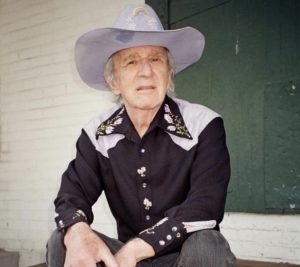

In the Pantheon of gay country music, Patrick Haggerty, and his band, Lavender Country, have no peer. In the first part of this two-part interview, Haggerty reveals the impetus behind his groundbreaking band.

You’ve lived in the Seattle area since the 1970s. What’s unique about Seattle that isn’t common knowledge? People think that San Francisco is the hub of gay land, and, in some ways, it is. However, Seattle was ahead of San Francisco at every turn. Seattle had the very first counseling service for homosexuals in the world. It was also the first to pass a gay non-discrimination ordinance. Again, for that one, we were ahead of San Francisco by a few years. Where did you hang out in Seattle? The Double Header I think was the prominent bar that comes to mind. It was an old-time, near-the-water-front, big bar, with an actual dance floor. The beer, and the dancing, was the draw there. In its heyday, Seattle actually had about ten to 15 gay bars. How did you enjoy spending your time when you lived in Seattle? I enjoyed a lot of sexuality, I have to admit. I stacked them up like corkwood. I was the queen of the bathhouse (laughs). But I regret the lack of intimacy with it all.

ADVERTISEMENT

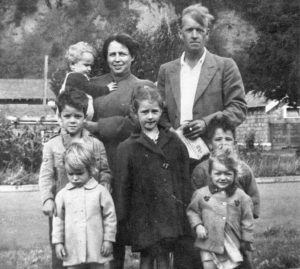

Where do you live now? I now live in a town called Bremerton. It’s about a half an hour ferry ride from Seattle. It’s been a navy town for about the past 120 years, and I married a navy man. But before that I lived in Seattle for almost 30 years. In terms of natural beauty, the area is like a doubly-blessed place. However, Seattle is pretty white. But, having said that, it’s mitigated by the fact that the minorities permeate the larger population. You mentioned that you’re married. Do you have children? My parents had ten children, so I grew up in a very robust family. I grew up with a kid on my hip. And when I came out as gay, and they said that if you’re gay you can’t have kids, that got me angry. But I made very good friends with a lesbian woman, and she didn’t want to raise a kid on her own. So, I screwed my courage to the sticking place, and I had sex with this woman—one time. And she got pregnant the first time. So I have a daughter, Robin. And, believe it or not, she has a son. So, I’m “Grandpa Patty.” I also have an adopted son. I adopted him when he was about eight. I was in a platonic relationship with his mother for a decade, but she always had custody of her son. We raised out children together, and she was a parent to my daughter as well. So, yeah, I did the whole dad thing—twice.

What does you son do? He works in the film industry—he’s a successful independent videographer. He moved to Brooklyn for his career when he was about 23-years-old, and I bawled every morning for six months. But he lives in Cuba now with his bride, who’s from there. She’s a leading stage actor. Raising a cis black man, as a white gay activist, had its challenges. But we remain quite close. He’s a disciplined and well-read Marxist, like me. And how about your daughter? My daughter’s also very successful. She’s a civil-service employee. She approves grants for people doing medical research on human subjects. She’s very busy now with all the Coronavirus studies coming through. What’s the most special experience that you had when you were in the Peace Corps? The one thing that stands out was when I got kicked out. That was very painful, particularly, in the memory of my father’s eyes—he was five years in the grave at that point. My father was just like Pa Kettle. I was just a screaming sissy, and my father figured it out when I was five. But he supported me, and he loved me in my sissiness. But he went a step further, because he loved me more and better because I was a sissy. It’s very hard to talk about him without getting emotional—I lost him when I was 17. So when I got kicked out, it was a very rude awakening. How dare you do this to me. Fuck you… It made me so angry.

Is Lavender Country the gay-rights achievement that’s the most special to you? Not really. I would say that Lavender County is a radical, socialist, political, homosexual band, and I put a lot of my ideas into it. I mean, I call for revolution in the songs. I’ve done it several times. For example: “Rise up, and rip this goddamn system down. ‘Cause there ain’t no hope, until you tear it down.” And I wrote that in 73’. What gay-rights achievement is the most important to you then? I might pick the two times that I ran for office in Seattle. One time I ran for city council, and the other time I ran for state senate. I ran both times with the backing of the National of Islam, if you could imagine. We did it as a form of protest, but I still got almost 20 percent of the vote. It was very challenging, but it was also rewarding and interesting. How was Lavender Country formed? I didn’t produce Lavender Country. The collective Stonewall experience in Seattle is what created the idea. The collective people gave the ideas for the songs, and they raised the money for both studio time and for publishing. But when we did it, we knew that it was the world’s first gay country album.

And then what happened after the first album? From 73’ to 2000, we had no recognition whatsoever. We ran around the country doing a few prides here and there. But the band died, and we went on with our lives. I mean, there wasn’t a market for radial queer country music. I had a family to raise and money to earn. The band wasn’t even on my mind; it was dead. I was actually living with my husband for, like, three years before he even knew I was in a band before. Speaking of your husband, how’s the Coronavirus affecting both of you? The Corona is driving me crazy, and it’s not like I don’t have an underlying condition or two. And my husband is black, and near 80, so we’re scared shitless. But if I do get it, hey, I had a great run (laughs). I had a really interesting… really engaging… really hot… life—the whole way. I’m very happy with the life that I’ve led. So if I go, I go. But once this is all over, I intend to get out on the road and do some more Lavender Country shows.